History

History

Introduction

"When you see smoke coming out of the town of Alcorcón,

don't think they bake bread;

pots and pans are”

(Popular children's song)

Alcorcón, located about 13 kilometres from the capital, and which is today one of the most representative cities of the Community of Madrid, was until the middle of the 20th century, a small town at the gates of the capital. Today, together with Móstoles, Leganés, Getafe and Fuenlabrada, they form the so-called Gran Sur.

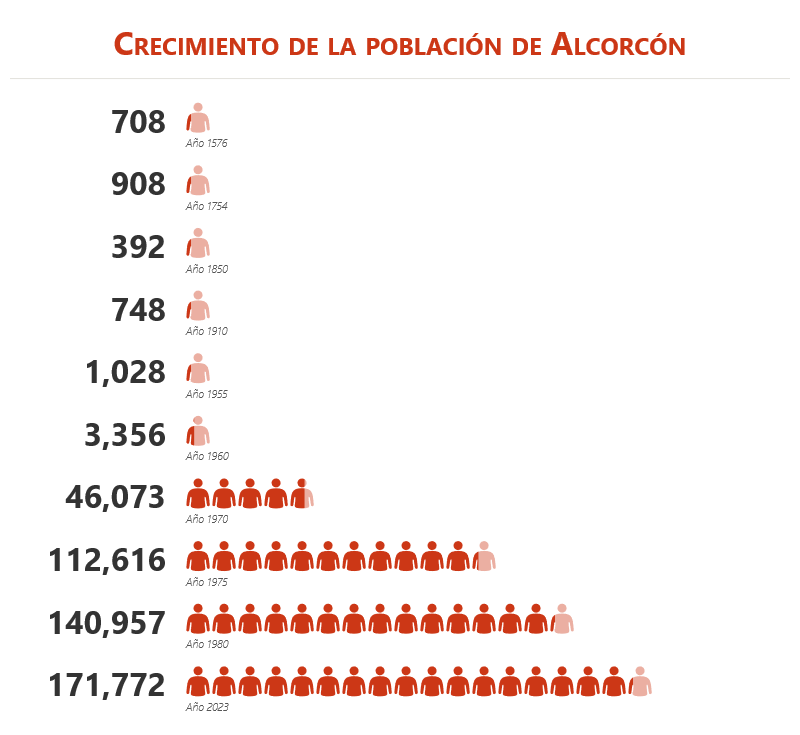

The 1955 census indicates 1,028 inhabitants and 959 legal inhabitants, a population that tripled in the 1960 census. But a decade passed and the number of residents multiplied by fourteen. In 1975 the municipality reached 112,616 inhabitants. The flood of emigrants from other regions of Spain was so significant that people lost awareness of what Alcorcón had once been, a small rural town on the Camino Real towards Extremadura, which had lived off agriculture and pottery, which gives rise to our emblematic stews, and whose way of life disappeared, dedicating the space to housing its growing population.

As of 2023, Alcorcón, according to INE data, has a registered population of 171,772 inhabitants , of which 82,226 are men and 89,546 women. It is a diverse community, with residents born in 147 countries. Data from the municipal open data portal .

History until the 20th century

According to the authors of the book Imágenes de Alcorcón. Un pase a través del tiempo , since prehistoric times, human beings have sought places close to water to settle, an essential element both for their own survival and for the animals they hunted and fed them. Few prehistoric remains have been found in Alcorcón. A small Paleolithic site was found around the Butarque stream and, in the source of the Canaleja, a stream in prehistoric times, flint flakes were found. There are also no documentary sources on the existence of Alcorcón during the Roman period in Hispania.

The territory of Alcorcón was located in the geographical area where the Carpetani lived, who, like the group of Celtiberian peoples, resisted Roman domination for more than 100 years. There is no reference to Alcorcón in documents from the Visigoth and Muslim periods, so it can be deduced that it did not exist or that it was an insignificant population.

Almost all sources agree that Alcorcón was an Arab settlement, placing its birth in the last third of the Reconquista, that is, in the Late Middle Ages, given the lack of earlier references. Its name appears, in fact, written for the first time as cañada de Alcorcón , which is mentioned together with the nearby Butarque when Alfonso VIII, at the beginning of the 13th century, delimited the territory of the jurisdiction of Segovia, indicating its division from that of Madrid. Its name will appear again very soon, in 1222, with the new delimitation carried out by Fernando III the Saint, of the Community of Land and Town of Madrid, a consequence of the constant struggle between Madrid and Segovia regarding their corresponding jurisdictions. Alcorcón is attached to Madrid, within the sexmo of Aravaca, that is, together with Pozuelo, Majadahonda, Boadilla, Leganés and the two Carabancheles.

However, it is quite possible that its original area, the adjacent and extinct population of Santo Domingo de la Ribota, which arose around the also disappeared hermitage of La Ribota from which it took its name, can be traced back to the High Middle Ages, around the 9th century. Some sources stress the large number of inhabitants that the settlement had in the time of Alfonso VI, surpassing those existing around 1949. Its subsequent population loss could be related to the disappearance of its character as a defensive enclave of the Muslim lines, when precisely Alfonso VI, during the course of the Reconquista, achieved the surrender of the King of Toledo after the conquest of Guadalajara, demolishing the lines of watchtowers in the border areas afterwards. References to the municipality of Alcorcón will not be found again until the 16th century with the appearance of the Relaciones topográficos of Felipe II .

It is the historian Julio González who tells us that this part of the Meseta was an unpopulated area, a situation that was further aggravated by the arrival of the Muslims. The depopulation of the south of the Meseta, where there was practically no rural centre up to the Tajo basin, was joined by the desertification of the north of the Central System, since the first Christian kings, to overcome their weakness, depopulated it up to the Cantabrian system, taking nearly two centuries to establish a border on the Duero River. Therefore, the Central System, with more than 400 km in length and with altitudes reaching 2000 m. was, for almost four centuries, a natural and effective barrier between the Muslim and Christian kingdoms and its natural passes and ancient roads were used by both in their respective attacks and incursions. Thus, according to Julio González, the routes used by the Muslim military expeditions never passed through Alcorcón.

However, Luis Palacios and José L. Rodríguez argue in their book Alcorcón. El despertar de una ciudad desde su historia (Alcorcón. The awakening of a city from its history) to the contrary: we can consider it very likely that it was Muslims who gave the place its name and also introduced the pottery work that has given its inhabitants well-deserved fame for several centuries. In short, it is possible to affirm (or imagine) that the primitive nucleus of population that was established in what is now the old town, on a permanent basis, was made up of Muslims or Hispano-Muslims, and that they did so around a watchtower and, perhaps, a mosque. Of course, the lack of references in Roman, Gothic and Visigothic times supports the theory of supposing it was created by Muslims between the 9th and 10th centuries, in the context of the struggles between Christians and Muslims around the cities near the enclave. As we know, the Muslims, coming from Africa, had penetrated the south of the Peninsula in the 8th century and then advanced into the interior until they occupied most of the peninsular geography.

Following this line, for several researchers such as Lorenzana, Madoz, Rosell, etc., the name of our city has an Arabic origin and comes from al-gor , alcor or al-kur , a word that means hill, mound or pass and was named thus because the town was located on a knoll. Therefore, Alcorcón would have been originally a watchtower or watchtower, on a knoll, destined to monitor the movements of the Christian troops and protect the Arab cities of Alcalá, Talavera and Medina Magerit (Madrid), relying on the orography of the Sierra Madrileña, a natural barrier that made it difficult for the Leonese and Castilians to harass Toledo.

The conquest of Toledo by King Alfonso VI in 1085 brought the Muslim Middle March under his control. Among the conquered cities was Madrid, which became a royal city and, within its boundaries, the territory of Alcorcón was included. In the capitulations between the Muslims and King Alfonso VI and, in relation to the cities that were handed over to the kingdom, Alcorcón appears, but they remained integrated into the kingdom of Toledo, property of the Monarch. Once these lands were occupied, the Muslims were expelled by the Christian invaders and displaced to the suburbs and, in this search for territories where they could live without problems, surely some group of Muslims settled in what is today our municipality, far enough from the Almudaina of Madrid and in an area with good clay and groundwater to carry out their pottery work. It is reasonable to think that this small town was a rural enclave, dedicated primarily to dryland agriculture, due to the quality of its land and the manufacture of pottery pieces, mentioned above.

The first medieval document that refers to Alcorcón dates back to 28 July 1208, in which the Cañada de Alcorcón is mentioned as a transit route for sheep and refers to the place where said cattle trail is located, which serves as a boundary for the Council of Madrid. As the dispute mentioned in said document was not resolved, new ones were made to confirm the limits of said Council, and in them the term Cañada de Alcorcón always appears. Six months later, on 12 December 1208, the ownership of the Cañada de Alcorcón, a thousand metres wide up to the Maro valley (Valdemoro), was confirmed in another letter to the Council of Segovia so that its flocks could move to the Council's property in the Valdemoro area. It was not until the time of Ferdinand III, 1217-1252, when the boundaries of the Council of Madrid became clearer, with three sexmos or rural compartments: Aravaca, Vallecas and Villaverde. Alcorcón was included in the sexmo of Aravaca.

In 1383 we have news that the town was handed over to D. Pedro de Mendoza and later returned to royal possession. This fleeting ownership of the royal property by a nobleman was due to the continuous conflict between the nobility and the successive kings of the House of Trastámara to see who would cede privileges and possessions. It was in 1485 during the reign of the Catholic Monarchs, when the division of the municipal terms of Alcorcón and Móstoles took place. Also in 1496 the boundaries between the jurisdictions of Madrid and Toledo were established (Alcorcón belonged to Madrid, and Móstoles to Toledo). We have to wait until the reign of Philip II (1556-1598) to have the first documented reference in which the existence of the Alcorcón Town Hall is discussed at length and is found in the Topographic Relations of Philip II which includes the description of Alcorcón dated January 17, 1576 and which says:

[…]The village, which has no more than 140 low houses made of mud and about 170 inhabitants, most of them poor; is a village of the town of Madrid and its jurisdiction, which is two long leagues away, being within the kingdom of Toledo; its name has always been Alcorcón, it is not known who its founder was and if the village was won from the Moors […] A place lacking firewood, therefore, of forests and pastures, they have farmland: wheat, barley and rye, with very little livestock (sheep) […] it is a windy place because it is on a high place; it is cool at all times and there have always been very old people there, over a hundred years old, who have lived very healthy. It lacks water because there are few wells and a fountain, from which they drink water, has little water, although good […]

It is also said to be a village in the Villa de Madrid and within its jurisdiction and royal domain . Antón Moreno and Martín Escolar are cited as mayors. It is said that 177 residents (approximately 708 inhabitants) lived there, occupying 140 houses. In Chapter II we read: […] the antiquity of said place has not been able to be found, nor who its founder was [...] . Therefore, in contrast to the more widespread opinion that Alcorcón is of Muslim origin, we believe that some groups of Muslim potters, a very common trade within the town of Madrid, due to the social and political pressure they suffer, sought a quiet place to be able to live and work around what could currently be the Plaza del Tejar in Alcorcón. Later, a group of Christians, due to the demographic pressure from the north of the peninsula and the facilities given by the Castilian kings, settled in the area that currently may correspond to the Prado de Santo Domingo and founded a small population, probably of agricultural origin.

It could be assumed that this group of Christians came from the north bringing a saint to protect them, Santo Domingo de la Calzada, or as he is known in Alcorcón, San Dominguín, due to his small size. And next to their adobe houses they built a small hermitage: Santo Domingo de la Ribota, or de la Rivera. In the Relations this hermitage appears as a place of great devotion, indicating that there must have been a population that had disappeared some eighty years ago, due to a great mortality rate , a very frequent circumstance during the Middle Ages, due to the poor conditions in which they lived. As a parish church, Santa María la Blanca appears. But neither its primitive origin as a mosque nor its later transformation into a Christian church are sufficiently dated. According to the restoration report of 1992, carried out by the Community of Madrid, we know that it is the most representative building of the place, located on a hillock, where the mosque is supposed to have been located. However, the first references are in the Relaciones de Felipe II, and the current church can be dated between the end of the 16th century and the beginning of the 17th century for the apse and the chancel, finishing its construction in the 18th century. According to this report, no remains of a church prior to this one have been found. The oldest date that appears on it is that of a tombstone (3 July 1595) that is under the current pavement.

The population increased progressively, perhaps because the Royal Road from Madrid to Extremadura and the Cañada road from Valencia and Toledo to Segovia passed through Alcorcón. Pedro Rodríguez Carbajo in his book Alcorcón in the Archives (years 1751-1761. The Cadastre of Ensenada), tells us that the passage of these roads through Alcorcón also caused inconvenience among the residents. Thus in 1761 they protested against the passage of the regiments of soldiers because the cattle they bring to Madrid eat the grass of the Prado de Santo Domingo and the residents cannot use it . Through the Cadastre of Ensenada (1751-1754) we know that, at that time, 227 residents (approximately 908 inhabitants ) lived in Alcorcón * and that there were 242 houses, many of them in ruins. But the most important thing is that the specific data of the existence of the important pottery business in our municipality already appears. At that time there were 54 potters working, whose names and surnames we know. We are told that they were day labourers who alternated their farm work with pottery, an activity that the people of Alcorcón were already proud of in 1575: […] what is made in the said place better than anywhere else is jugs, pots, jars and small pots, and this is made so well and the clay is so suitable that they are taken to many far-off places, and are highly regarded throughout the kingdom […] . We also know that there were 2 taverns, 2 inns, 2 grocery-haberdashery shops and a butcher shop.

[* Note . In the census of residents only those who owned property and were obliged to contribute were registered. Inhabitants were all those who resided in the place (neighbors, nobility, clergy, indigents and other people who lived around each neighbor)] .

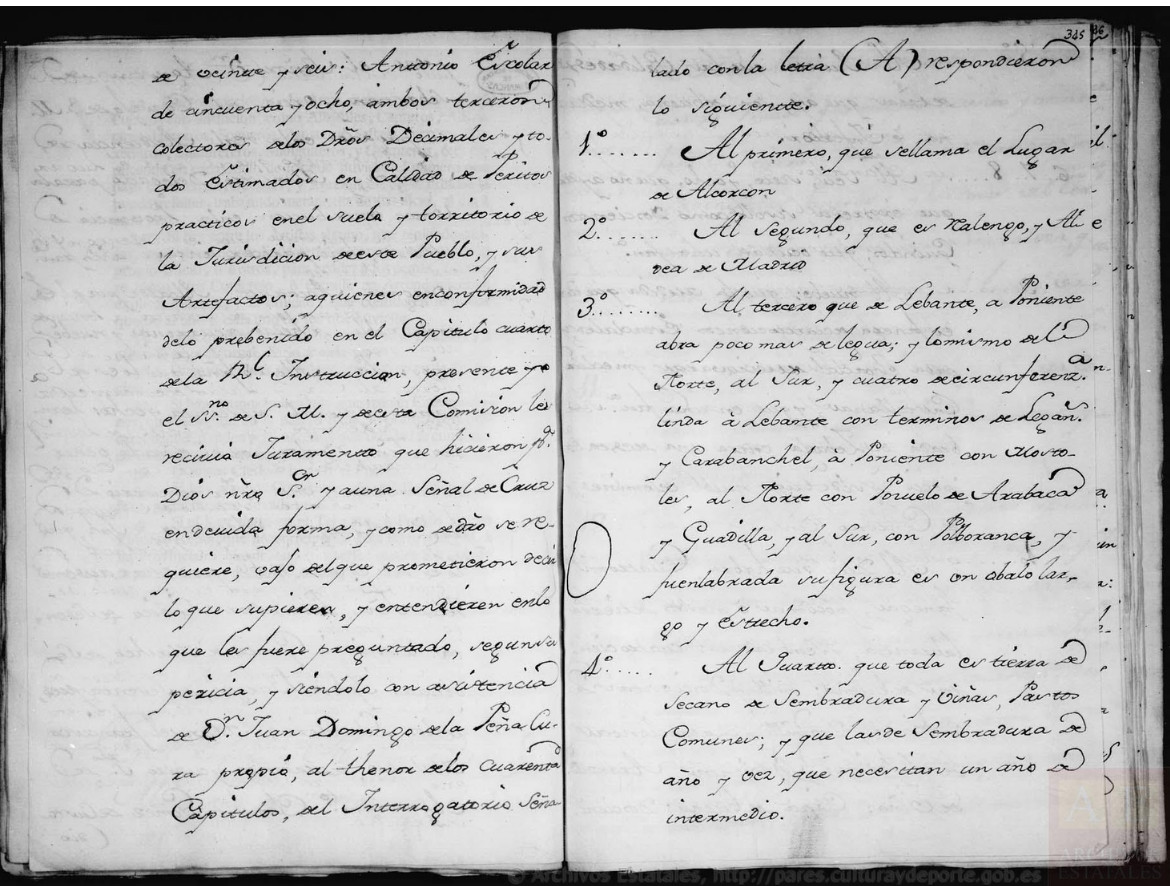

Regarding the extension of the municipal term, the Cadastre of Ensenada states that it measures a little more than one league (5572.7 meters) both from east to west and from north to south, and four in circumference. Its boundaries would be, to the east, Leganés and Carabanchel, to the south with Polvoranca and Fuenlabrada, to the west with Móstoles and to the north with Pozuelo and Boadilla. It defines its shape as a long and narrow oval , as we can see in the following image:

According to the aforementioned book Alcorcón. The awakening of a city from its history , […] life in Alcorcón must have changed little over the course of the 17th and 18th centuries. The townspeople continued to focus their efforts on agricultural work, basically the cultivation of cereals, and the pottery industry […]. However, this being true, we must not overlook the possibility that the town experienced a certain boom during the 17th century, a period during which several plays were performed at the Court in which the town appears as the axis or occasional location of the development of the plot. However, in the following decades, Alcorcón experienced a serious decline as a consequence of endemic famines and the War of Succession that took place after the death of Charles II of Austria.

From the reign of Philip II onwards, documents on Alcorcón became more numerous. Thus, during the so-called Golden Age, Alcorcón appears in several literary works, such as La Tarasca del Alcorcón/ El Alcalde de Alcorcón or El Ollero de Alcorcón . We also find a source of information, of a costumbrista nature, in the protocols deposited by the notaries that cover the periods from 1571 to 1768. Some of them can be consulted in the Historical Archive of Protocols of Madrid .

In 1812, most of its inhabitants left the town due to food shortages and illness. Its recovery was very slow and in 1847-50 its 105 inhabitants (392 souls) lived in 80 houses distributed in 4 streets and a square, according to Pascual Madoz's dictionary , which also states that saturnine colic and lead poisoning were frequent, pointing to the glass manufacturing process as a possible cause.

In 1890, with the entry into service of the Navalcarnero Railway, the recovery of the population that had begun in the mid-19th century was consolidated, at which time Alcorcón began to experience a gradual growth that would accelerate during the course of the 20th century.

Alcorcón in the 20th and 21st centuries

In 1910, it already had 748 inhabitants and its urban infrastructure was 130 houses. It was at this time that the first Municipal Ordinances came into force, as the first document regulating local activity, mainly in terms of urban policy and public health. It is now when the different provisions regulating the pottery industry, with such a long tradition in the municipality, and whose location was outside the city centre, are outlined. The main occupation of the population continued to be agriculture and sheep farming, which was complemented by some industries such as soap making, oil storage and mainly pottery making of recognised quality at least since the 19th century. At the end of the civil war, after the first third of the 20th century, a series of planning plans began to be drawn up aimed at reconstructing the urban planning of the city and its surroundings. Alcorcón, which is located near Madrid, is included in the different plans, both of the Central Administration and of the Madrid City Council. The aim was to decongest the capital by promoting the formation of a series of satellite cities, separated from the capital by a green ring that would surround the city. This plan would assign Alcorcón a residential function within the population centres of the southern area. It was the first municipal plan of a metropolitan nature that included Alcorcón as a means of decongesting Madrid. Until the 1960s, Alcorcón maintained its rural structure, whose economy was based on agriculture and pottery, the latter in clear decline.

It was not until the middle of the 20th century, specifically the beginning of the 60s, that the municipality began the path that has led it to become the great city that it is today. At that time, the urban development of Alcorcón began with the start of the San José de Valderas neighbourhood and the construction of the town centre. In 1958, the construction of the San José de Valderas neighbourhood began, in the area near the Castles, located about two km from the town centre and separated from it, promoting a speculative operation in this area. Likewise, in 1959, a line located to the south of the centre was divided into plots, creating three areas on which a series of houses were built in which the working classes that began to arrive in the municipality settled.

In 1968, the General Plan was approved, which was accompanied by the approval of various partial plans (the Eastern Partial Plan, Urtinsa, etc.) that would encourage the establishment of new buildings and industries. A significant number of young families and couples began to move in, which in turn generated a large growth. The population went from 3,356 inhabitants and 800 homes in 1960 to 46,073 inhabitants and 16,525 homes in 1970. In 1971, Alcorcón officially went from being a town to a village, and there was a spectacular growth in the population. In 1975, it had 112,048 inhabitants , and by 1980, there were 140,957 people and 44,573 homes. From that moment on, the municipality has continued to grow in a more moderate and rational way, with good infrastructure and equipment appropriate for its size. Since April 2005, it has been officially classified as a large city. In 2023, the number of inhabitants of Alcorcón is 171,772.

Below we show an image that reflects the demographic growth of Alcorcón since 1576:

Selected bibliography:

- Alcorcón City Council. (1985). Now a plan for the future. General Urban Development Plan. The City Council.

- Cantó Téllez, A. (1958). Tourism in the province of Madrid. [sn].

- COPLACO. (1981). Urban territorial planning guidelines for the revision of the General Plan of the Metropolitan Area of Madrid . Planning and Coordination Commission of the Metropolitan Area of Madrid (COPLACO).

- González, J. (1960). The Kingdom of Castile in the time of Alfonso VIII. CSIC: School of Medieval Studies.

- Images of Alcorcón: A walk through time . People's University of Alcorcón.

- López, T. (1788). Historical geography of Spain. Province of Madrid: second volume . Madrid: By the widow of Ibarra, son and company. Digital link: https://bibliotecavirtualmadrid.comunidad.madrid/bvmadrid_publicacion/es/consulta/registro.do?id=441

- Madoz, P. (1849). Geographical-statistical-historical dictionary of Spain and its overseas possessions (Vol. 1). Imp. Pascual Madoz. Digital link: https://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/detalle/bdh0000176537

- Palacios Bañuelos, L., & Rodríguez Jiménez, JL (1999). Alcorcón. The awakening of a city from its history. Ed.

- Puerta, Juan de la fl. (1699-1724) The Ollero of Alcorcón, in Loa, and celebrity of the royal birth of our prince, and lord D. Luis Primero of Asturias explains his great love in this humorous romance . Ed. Juan de la Puerta in the seven revolts [sic]. Digital link: https://datos.bne.es/edicion/bima0000108090.html

- [ Relations of towns of Spain made in the time of Philip II, from 1574 to 1580 ] Digital link: https://rbmecat.patrimonionacional.es/bib/678

- General Responses of the Cadastre of the Marquis of Ensenada (1750-1754) . Digital link: https://pares.mcu.es/Catastro/servlets/ServletController

- Rodríguez Carbajo, Pedro. (2008). Alcorcón in the archives (years 1751-1761. The Cadastre of Ensenada) in the Regional Archive of the Community of Madrid . Jiménez de Gregorio Institute of Historical Studies of the South of Madrid.

- People's University of Alcorcón, & Alcorcón City Council, Department of Culture. (1997). Images of Alcorcón: A walk through time . People's University of Alcorcón.